There is no singular concept of “traditional” architecture, for each culture has its own cultural heritage, traditional forms, and architectural language. But what is it about each culture’s architecture that makes it unique? And what qualities, if any, span those cultural boundaries, becoming shared building traditions?

These are just a few of the questions Professor Kate Chambers has asked the fourth-year students in her studio course to investigate this semester. The exploration of non-Western architecture is a common theme across spring semester fourth-year studios, and Chambers has chosen to do so through the lens of the city of Aleppo, Syria.

“The goal of the studio is two-fold,” writes Chambers in the course description. “First, to open your minds to architecture outside of the Western canon, to understand how your classical education can be applied globally with intention and care for local culture and traditions. Second, simply to get excited about architecture, to enjoy the study and implementation of new ideas, to use your knowledge, passion, and creativity to create a vision of peace and beauty for the future of Syria.”

Elisabeth Hanley ‘23, one of Chambers’ students, chose the Great Umayyad Mosque in Aleppo as her subject.The first project of the semester—which wrapped up with a review in early February—contained two phases. In the first phase, each student was asked to analyze a historic building in Aleppo by documenting its location in the city, building type and typological elements, historical presence in the city, and current condition. The second phase of the project involved comparing the building (or part of the building) to a Western counterpart with a similar use or form, and composing a comparative plate to help analyze the two buildings from urban to ornamental scales.

“This minaret was destroyed in 2013 during the Syrian Civil War, but there is currently an effort to rebuild it. I felt that this structure is exemplary of the resilience of the Syrian people and their determination to maintain a strong sense of cultural identity.”“I chose this as it is the central mosque in the city, and I was interested in studying Islamic architecture as an introduction to my study of Syria,” said Hanley. “At the outset of the project, Professor Chambers encouraged us all to think about what we wanted to learn from our analysis when deciding where to focus our efforts. I chose to focus my comparative study on the minaret, as I was fascinated with the layering of detail on the tower during my analysis as well as the importance of the call to prayer in the Islamic tradition and the prominence the minaret has in the city.

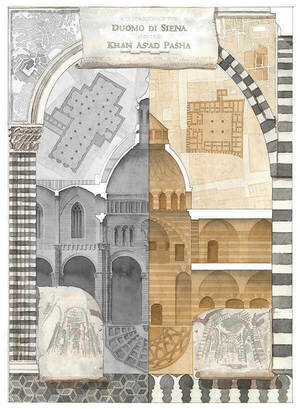

Meanwhile, Hanley’s fellow classmate Angelica Ketcham ‘23 focused on a 17th-century Ottoman palace in Aleppo, and also compared a Khan in Damascus to the Siena Cathedral. In her analysis of the palace, Ketcham paid particular attention to its courtyard elevations, volumetric representations of important or public space, and use of geometric patterns. The Khan-Cathedral comparison plate, on the other hand, focused more specifically on how the two buildings used ablaq masonry in dome construction.

“I left this project with a more thorough comprehension of some of the essential values of Syrian and Islamic architecture and urbanism,” said Ketcham. “The non-Western studio is extremely valuable to students. In order to be equipped to design in any context and tradition, for any community, it is essential that we are exposed to a wide and global variety of vernaculars and styles.”