Inspiration for architecture thesis projects may stem from various sources including academic passions and personal connections. Such was the case for South Carolina native Phillip Smith’s graduate thesis project, a counterproposal for the design of the International African American Museum (IAAM) located in Charleston, South Carolina.

“Coming soon on one of the most important sites in American history, the place where more enslaved African captives arrived in the U.S. and were sold than any other location, the IAAM will present the largely under told experiences and contributions of Americans of African descent,” reads the banner on the IAAM’s website. The IAAM is a hard-won victory for the city of Charleston, South Carolina as it is at last coming to fruition after 30 years of consideration. After the 2015 Charleston Church Massacre, when an African American church was targeted by a gunman and nine parishioners murdered, former Mayor Joseph P. Riley, Jr. recognized the timely need for a place to mark the significance of African Americans in Charleston and catalyzed concrete plans to build the museum. Fundraising efforts raised $75 million and plans to break ground on the museum were scheduled to begin in May 2019.

Even though tragedy was the impetus to build the IAAM, the museum is more than just a response to a devastating event - an event that will likely be engraved in the minds of many Americans for life. Instead, the museum represents an opportunity to shift public perception of Charleston and to tell a story that honors the African people who were forcibly brought to the shores of South Carolina, cemented the area’s economy, and still live there today. Amid some controversy on how this story would be best articulated in the museum’s design, Smith completed his counterproposal that celebrates the contributions of enslaved Africans to the architectural heritage and building traditions of Charleston, reckons with the horrors of slavery, and lauds the courage and bravery of those subjected to the transatlantic slave trade.

Design

Smith’s design, like the current IAAM design, will sit on the river at the site that was once Gadsden’s Wharf, a pier that welcomed hundreds of thousands of enslaved Africans from 1780 to 1810. Up to six ships could dock at once on the 800 foot long wharf. This site is often referred to as “sacred ground” since many African captives died while waiting, sometimes for months, to be auctioned. Smith plans to honor this through his design by evoking Roman architecture. “Where the wharf is…[I included an element similar to] Bramante’s Tempietto unfolded. The significance being that the tempietto in Rome marks the symbolic location of Peter’s crucifixion. The tempietto being unfolded is symbolic of this very sacred site and serves to highlight the purpose of this museum.”

Symbolism in design is plentiful here as Smith, maintaining some of the programming from the current design, has been thoughtful about incorporating elements intrinsic to the African experience in America. After an introduction exhibit, the journey through the museum starts with an African Roots exhibit intended to highlight life in Africa before the transatlantic slave trade. From African Roots, there is a threshold leading into the Atlantic Connections exhibit and then to the South Carolina Story exhibit which places visitors on the footprint of the historic Gadsden’s Wharf.

The current museum design lacks a performance space. Smith’s counterproposal, acknowledging the importance of performance to African American culture, has placed the Jenkins Orphanage Band Memorial Hall at the center of his design. Both designs include a reference to the Brookes slave ship diagram which depicted the stowage of slave ships. Smith references this in the design of the ground floor where he includes piers and heavy masonry vaults. The space between the columns in the middle aisle is twenty-five ft which is the width of the slave ship depicted in the Brookes diagram.

Retelling and Representing Race

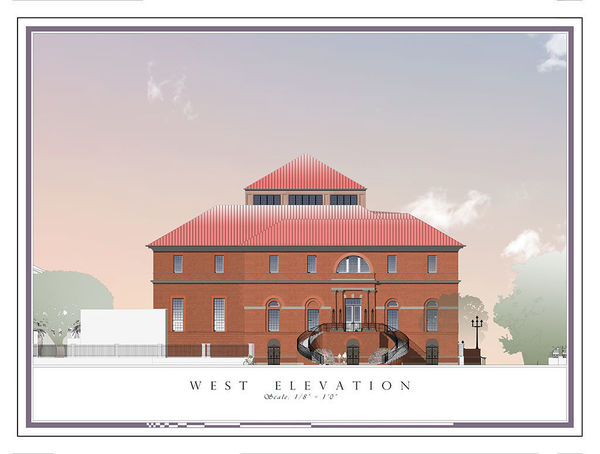

Smith states that he was “not really invested in high classicism with this design. It is informed by classical elements.” By employing these elements he hoped to weave the museum into the contextual fabric of Charleston and its more traditional architecture. This also serves as an opportunity to pay homage to enslaved Africans who were charged with building many of the traditional buildings that have become synonymous with Charleston. For Smith, it was important to highlight that slaves likely had a skill set for building traditionally when they arrived in North America and thus are essential to the understanding of traditional building in this country. “Architecture belongs to the African American community,” Smith remarks while explaining that 85% of the black sacred architecture in Charleston was influenced by traditional design.

Smith also notes that his counterproposal does not include African imagery contrary to what may seem appropriate given the nature of the museum. As an African American far removed from the continent of Africa, Smith argues that it would be nearly impossible to represent the richness of the many African cultures in one space. Since there are 54 countries in Africa and hundreds of subcultures and languages, selecting just one symbol risks being disingenuous. Instead this was an opportunity to incorporate symbols that speak to more current African American culture, specifically iron work that honors the work of people like Philip Simmons, a noted African American blacksmith from South Carolina.

For Smith designing a space that represents the legacy of the African diaspora in South Carolina is not only an opportunity to celebrate African American history but also to reclaim a space built by slaves. Smith’s counterproposal acknowledges this country’s sordid past whilst praising those who endured and those who would go on to construct beautiful cities like Charleston.